March 16, 2025

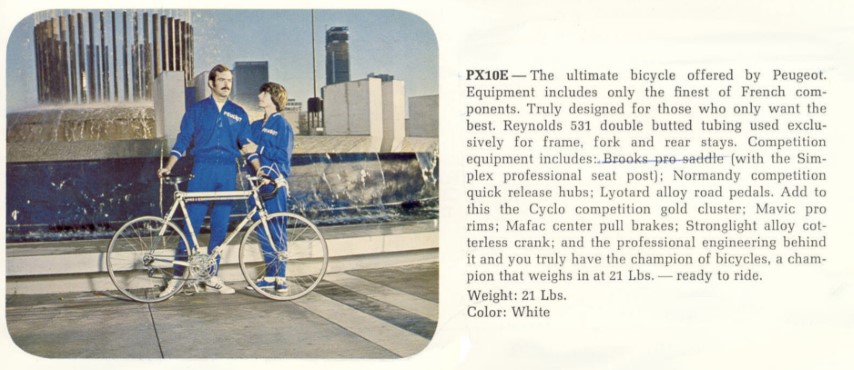

Peugeot catalog circa 1971. I'm not sure what message was intended by this picture. Sometimes, the past is a foreign country.

The Peugeot PX10 holds a unique place in cycling history and helped to define cycling for a generation of Americans. It's hard to believe today, but from the 1920s until 1970, bicycles in America were mostly viewed as a child's toy. Grownups drove cars, kids rode bikes. That started to change in the 1960s as manufacturers like Schwinn and Raleigh marketed 3-speed cruisers to adults as a means of exercise. But these were heavy steel bikes with few if any lightweight alloy components.

Although common in Europe, lightweight racing or touring bikes with drop bars and derailleurs were a rarity in the U.S., found almost exclusively among the professional and amateur racing circuit. Almost all were handmade in by small bespoke manufacturers. But something shifted in the American psyche around 1970. Suddenly, everyone wanted a 10 speed bicycle. This was the beginning of history's second great bike boom .

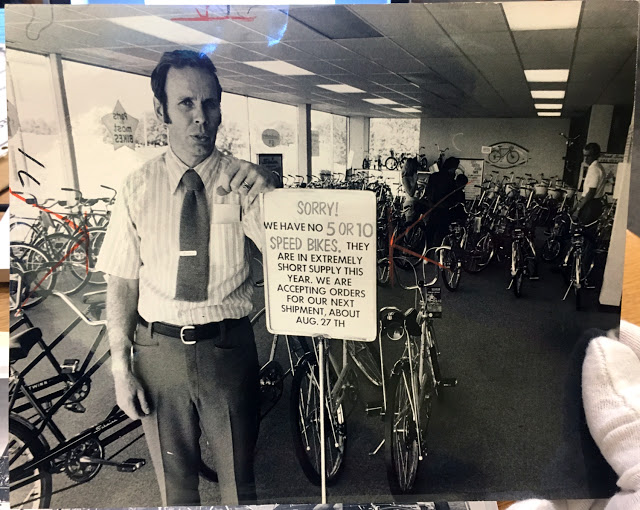

Park Schwinn in Maplewood was an early Peugeot dealer. The company later became Park Tool. This picture is from the height of the bike boom in 1971.

Initially, cyclists had to chose between the venerable, cheap, and extremely heavy Schwinn Varsity or very expensive lightweight imports from the UK or Italy. Peugeot, which had been making bicycles in France for nearly a century, was one of the first brands to bridge this gap with a wide selection of models from the ubiquitous UO8 to their top model, the PX10.

Priced well below its British and Italian competition, the PX10 was built with the same Nervex lugs and Reynolds 531 steel but used entirely French components like Simplex derailleurs, an AVA stem, and a Stronglight crankset instead of more expensive Italian components.

But the PX10 offered a more relaxed geometry than other racing models, which made its handling more suitable for longer rides and rougher roads. It took bumps and potholes better than its twitchier Italian and British cousins. As I understand it, this was because French roads were often cobblestones and, even in the 1960s, still had craters from WWII. But also, French racers had a philosophy of training and racing on the same bike, so their racing designs had to withstand daily abuse.

All of which explains why PX10s, despite being marketed as a racing bike, tended to be well loved and well ridden--seldom earning "garage queen" status. Riders like Sheldon Brown, who converted his into a 3-speed commuter, made all sorts of modifications for touring and commuting or added upgrades for racing. Today, it's difficult to find a used PX10 for sale--people tend to hold onto them. I looked for several years until 2023, when I finally found one in my size. (And then I immediately found another, but that's another story.)

My first find seemed to have spent 40 years gathering grime in a garage in Shoreview, it's ivory paint caked grey. Peugeot models and dates of manufacture are difficult to identify because their serial numbers mean nothing and the only identifier is usually on a scrap of paper taped to the bottom bracket, long since lost. But, you can tell this is a PX10 because it has Reynolds stickers, chromed fork blades, and chromed stays. Other details are a little less straightforward. For example, both the fork crown and the crankset are different from Peugeot's specifications. Throughout the bike boom, Peugeot was famous for substituting parts to meet demand.

Likewise, the only way of knowing this is a 1971 model is because of the position of the Reynolds sticker on the seat tube and the types of lugs. But still, that's just a guess.

After stripping the bike down, I got to work on cleaning and touching up the paint. The chrome cleaned up nicely after a bit of scrubbing with aluminum foil followed by metal polish. I also polished the paint and waxed the entire frame. Now it was time to start bolting on parts.

I've previously expressed my disdain for Simplex derailleurs. The PX10's is probably the worst example of the lot, the Simplex Prestige. In order to save weight, the Prestige used delrin plastic instead of metal. Over time, the plastic invaribly cracked and the derailleur self destructed.

Unfortunately, the PX10's Simplex dropouts aren't compatible with other brands of derailleurs because the hanger lacks threading and a notched stop required by most Campagnolo, Suntour, and Shimano mechs. Luckily, the Shimano Crane derailleur has two tabs on either side of its mounting bolt which allows it to function with a Simplex dropout. All I had to do was tap threads into the mounting hole.

The cranks and bottom bracket also presented unique challenges. French cranksets used different threading than everyone else, so before I could even remove the crank, I had to find a French crank puller. Luckily, I found an early Park Tool puller on eBay with both French and English threading. Once the cranks were off, I could rebuild the bottom bracket which, of course, also used French threading.

As I mentioned earlier, the original specifications for the PX10 called for a different crankset, the Stronglight 93. The 93 was basically an updated version of the 49D and lacks the small bolts that connect the crank to the spider. Both have the same beautiful pentagram design.

Stronglight actually invented the cotterless square tapered crankset in 1933, a design which still predominates today. The 49D was first introduced in 1949 and may well be a few years older than this bike. In any case, it works great and looks amazing.

While rebuilding the Stronglight headset, I was shocked to discover a wooden dowel inside the fork at the bottom of the steerer tube. This is in fact a cornouillet, meaning "made from dogwood". It's mysterious purpose seems to have been as a fail safe in case the fork crown suddenly broke while riding--the cornioullet would hold the fork together long enough to safely dismount. Whether this was ever an actual problem in steel racing bikes is hard to say, but somehow it became customary for mid-century racers to jam wooden plugs into their forks, often using bits of broom handles. At some point, Peugeot and other manufacturers began installing these at the factory, using dogwood because of its hardness. Probably by 1971 this practice was nothing more than superstition, but who am I to question tradition? I jammed the cornouillet back into place.

Two pieces I didn't keep were the PX10's original stem and handlebars, both of which have a reputation for failure. The AVA stem, in fact, has earned a reputation as the DEATH STEM, which is possibly a bit overdramatic. It took me a while to find a suitable replacement because, once again, stems on French bikes use a slightly diffent diameter than everyone else.

The PX10's brakes are Mafac Racers, a very French version of a centerpull brake. Unlike most vintage brakes, their pads are mounted on unthreaded posts, similar to cantilever brakes. This makes them much more adjustable but also extremely finicky. As I understand it, the design was necessary because some vintage wheel rims had non-parallel brake surfaces.

It's possible to get reproduction pads with the four circular contact points, but I decided instead to used Kool-Stop Eagle II pads, which stop great and don't squeak.

As with most of my bikes, I swapped out the downtube shifters for Suntour barcons, which are probably the best shifters ever made. For the handlebars, however, I decided to try something different--shellacked cotton bar tape.

Back in the 70s, handlebars were taped with either plain cotton or slippery cellophane tape, neither of which offered much padding. The cotton was grippier, but tended to rot over time. Somewhere along the way, riders started shellacking cotton tape to make it last longer and repel moisture. I used Newbaum's tape and bought a fresh can of shellac from Menards--it's important to get a batch less than 6 months old so that it doesn't cure up sticky. I used some colored embroidery thread in Peugeot's Tour de France colors to secure the ends of the tape. I think it turned out pretty great.

Many early 70s PX10s shipped with Brooks Professional saddles from England. This one had an Ideale 90 saddle, which was made in France. Ideale saddles date back to 1890 and their model 90 is quite similar to the classic Brooks B17. The leather was dry, but a generous application of Brooks Proofhide freshened it up.

The PX10 originally shipped with either tubular wheelset or the clunky clincher rims that came on this bike (which technically made it a UX10, a distinction that's been forgotten over time). Both versions featured distinctive high flange Normandy hubs. I decided to upgrade to Campy hubs laced to Rigida clincher rims for a lighter and stronger build. French racing bikes in the 70s used 700c wheels, which is still the standard today, opening up a huge selection of modern tires. I chose my favorite road tires, the Continental GP Four Seasons in a comfy 28mm width. The frame could easily accommodate up to 32mm wide tires as well.

In the year and a half since I built it, I've really enjoyed riding this bike. It's comfortable yet quick and it always seems to attract compliments. Like my other Peugeot, it has a certain joie de vivre that makes every ride just a little bit more awesome.

Thanks for reading. Keep the rubber side down.

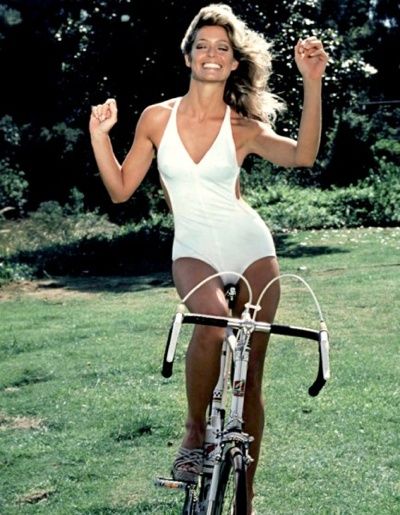

Farrah Fawcett marketing the PX10 (in a swimsuit?) in the early 1970s. Bike boom marketing was often fairly sexist.

Sheldon Brown on his PX10.

My 1971 PX10 before resotration.

After a bit of cleaning and touching up

The original Simplex derailleur

The Shimano Crane Derailleur

Vintage Park Tool Crank Puller

The Stronglight 49d crankset

The Stronglight 49d crankset installed on the PX10

A wooden plug, or "cornouillet" from the steerer tube

Mafac "Racer" brakes

Handlebars with shellacked cotton bar tape

The original Ideale 90 leather saddle

The completed build